Published in Greek in the local newspaper “To Galaxidi” March 2021[1]

-------------------------------------------------

Save the date: 27 August 2021 Galaxidi

Film Screening: of passage to Europe by Dimitra Kouzi, WINNER for Best documentary, at the San Francisco Greek Film Festival 2021, Special Jury Award Documentary at the Los Angeles Greek Film Festival

Both by luck and design, a privileged choice, dictated by the pandemic, to stay in Galaxidi since late August 2020, offered us the pleasure for an even more unique in-person world premiere for my film, Good Morning Mr Fotis![2]Being in Galaxidi throughout this period gave us another blessed opportunity – to enjoy a swim in the sea almost every single day throughout the winter![3]

Everyone who was there at the October 2020 screening expressed their wish for something more.[4]

A few short hours after the screening, Mit[5] wrote a very helpful, to me, article/review, titled ‘Hosting Refugee Children in Greece’.[6]

The public’s response in Galaxidi, Mit’s review on the morning following the screening, a 5 month tutorial with him and later Tue's Steen Müller’s review, (two months later), prompted me to create a new film, during the lock-down.[7]

passage to Europe was selected to be screened at the Los Angeles Greek Film Festival on 10–20 May and at the Greek Film Festival in Berlin on 1–6 June (both events online).[8] The first live in-person screening in Greece will take place at Galaxidi on Saturday 27 August.[9]

Mit's text might very well have been subtitled: ‘A guided tour to the new Athens’. Viewers, including the Greeks who don’t live in the city centre nor pass by Vathi Square, where the film is set, embark on a kind of a ‘journey’ out of their bubble and to this neighbourhood, which has dramatically transformed in the last ten years. The area is now almost exclusively inhabited by immigrants and refugees. This is a common occurrence in many European cities, but in the suburbs;[10] here, it has happened in the very heart of the city. It is the neighborhood that is the context in which the story takes place, that creates the conditions, that made me think and make a film. My own setting, my environment, is what determines the conditions of my life; it gave me the opportunity to think about making a film; yet my broader environment in Greece was definitely not what helped me turn my vision into reality – or will help me to make my next film.

The issue of a lack of a conducive framework often arises in our discussions. We are lucky here in Galaxidi to have a reference to a very specific and easy to grasp framework once in place in the village – a framework developed by seamen, which was the differentiating factor for Galaxidi. What would these seamen say after the second screening, in August 2021, sipping their coffee in the three cafes (Krikos/Hatzigiannis/Kambyssos) on the Galaxidi port?

Mit argues that in the 70 minutes of the original film there was not a strong enough link to the refugee issue,[11]especially for Northern European viewers who are not immediately aware of the connection, but will certainly face the issue eventually, as it is in Northern Europe that almost all the children in Good Morning Mr Fotis dream of living in ten years’ time.[12]

So my goal was to condense the action and highlight the immigration issue. Mit proposed me to give the film an open ending which I did without any further filming taking place. Mr Fotis should not be alone in carrying the load, when every year he welcomes a new class of children of multiple nationalities, often with non-existent Greek, making us complacent and creating the illusion that, as long as there are teachers like Mr Fotis, everything is fine. For the different end I used black and white pictures by Dimitris Michalakis.

Shorter durations are more ‘portable’. They afford much more freedom. It’s like travelling light.[13] Evaluation – what goes out, what goes in – is hard and puts you to the test, as it requires exacting standards and constant decisions. In passage to Europe, as the new film is called, the beginning changes, the end changes, and the duration decreases (from 70ʹ to 48ʹ).

In fact, all children wish to leave for countries that do not have their own ‘Lesbos islands’, writes Mit (10/26/2020). This adds moral value to Greece’s efforts, he adds. He supposes that pupils may well take for granted what Fotis does (he agrees on this with Tue Steen Müller from Denmark and his review of the film);[14] viewers do, too, I add. At the same time, we all wonder, ‘Why aren’t there more people like Fotis?’

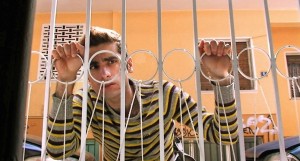

passage to Europe deals with the issue of immigration in the light of social integration, with respect for diversity, not in theory but in practice.

Fotis Psycharis has been a teacher at a public school in the heart of Athens for 30 years. The majority of his students, as in the wider region, are children of immigrants and refugees from Africa, the former Soviet Union, the Balkans, the Middle East and Asia, who often see Greece as an inevitable stopover to other countries of Europe. Cultural differences, the lack of a common language, the overcoming of these challenges, Ramadan, Bollywood, the unexpected things that occur during rehearsals for the performance they are preparing to mark their graduation from primary school, the children’s dreams and insecurity for the future, all make up a unique everyday reality in this class, which consists of 17 students from 7 different countries. Aimed at an adult audience, the film provides a rare opportunity to experience life in a public school in today's Greece, which is a host country for immigrants and refugees.

It is an observational documentary. Both Mit and Tue agree on that. I observe a reality that makes me think. What does it mean to grow up in two cultures, in a country other than where you were born? What can we learn from similar cases in history? To create the present, Mit says, one must go back to the past, and from there to the future. To create the future it takes creativity in the present, rather than taking comfort in the past, I believe. What does that mean for a place such as Galaxidi, a formerly vibrant shipbuilding, ship-owning, and seafaring town?

In early 2017, when I started making my film Good Morning Mr Fotis, I was planning for it to be 20 minutes long, reasoning that ‘smaller’ meant ‘safer’. I sought to obtain a filming permit from the Greek Ministry of Education to film in the school.[15] However, I went on to shoot a lot of more good material. So much so that it is enough for a third film, if only funding is secured.[16]

During making passage to Europe, things happened that can only happen when you actually do something. Now I think, combine, see differently, take more risks. I have my gaze fixed on this issue, which seems to have fallen out of the news[17] but is bound to return with a vengeance, aggravated by the pandemic. In mid-March 2021, Turkey-Germany negotiations resumed,[18] with the former demanding compensation in order to continue to ‘keep’ refugees outside of the EU.[19]

I feel grateful for making this journey in space and time together with Fotis and for capturing this moment on film twice. It's a diary, a proposal to look at a story that concerns us all in Europe. In the film, one school year ends and the next one begins. Yet, it doesn’t come full circle and end with the end credits. My intention was for it to be an open circle, a relay, encouraging viewer interpretations, continuities, thought and action.

Dimitra Kouzi

Galaxidi, March 2021

[1] Translated into English by Dimitris Saltabassis

[2] I would like to thank all viewers who showed up at the Youth House on 25/10/2020 to watch my film, Good Morning Mr Fotis, an audience of some 35 indomitable persons who braved the fact that the screening was ‘al fresco’ in the courtyard in the evening, with social distancing and masks, in a freezing maistros (mistral, the north-westerly wind). Not only that, but they stayed on after the screening for a lively Q & A! For me, this was a magical moment, and I would like to thank everyone who was part of our audience – an indispensable element to a creator! Even more so during a time such as this, when everything takes place online! I was fortunate to show my film to people most of whom have known me since I was a child, and my parents and grandparents, too.

[3] ‘Sure, the sea is cold,’ is the standard reply – and that’s precisely what makes a brief winter swim (5–15’) so beneficial! Let alone how great you feel after you pass this test!

[4] Good Morning Mr Fotis, documentary, 70', Greece, 2020, written, directed, and produced by Dimitra Kouzi • goodmorningmrfotis.com, Good Morning Mr Fotis: Greek Film Centre Docs in Progress Award 2019 21st Thessaloniki Documentary Festival • Youth Jury Award 2020, 22nd Thessaloniki Documentary Festival • Selected to be nominated for IRIS Hellenic Film Academy Award 2021 for Βest Documentary.

[5] Mit Mitropoulos, Researcher, Environmental Artist, Akti Oianthis 125, 332 00 Galaxidi, Municipality of Delphi [email protected].

[6] ‘Hosting Refugee Children in Greece’, To Galaxidi newspaper, November 2020.

[7] This ‘discussion’, which could only take place thanks to the fact that both I and Mit were constantly in Galaxidi due to the pandemic, was the main reason why I decided to make passage to Europe.

[8] Earlier on, the film was screened at the San Francisco Greek Film Festival on 16–24 April 2021.

[9] passage to Europe, documentary film, 48ʹ, Greece, 2021. Written, Directed, and Produced by Dimitra Kouzi ([email protected], at the moment Parodos 73, 33 200 Galaxidi, Municipality of Delphi).

[10] Jenny Erpenbeck (author), Susan Bernofsky (translator), Go, Went, Gone, Portobello Books, London 2017. Set in Berlin, where immigrants and refugees have also been received, the book is based on a large number of interviews with immigrants and their stories. The main character is a solitary retired university professor, recently widowed and childless. One day he suddenly ‘discovers’ the existence of refugees in his city; through the fellowship that develops and the help he gives them, he finds new meaning in his life, which seemed to be over when he retired.

[11] The refugee/immigrant issue will historically always be topical – all the more so now that the revision of the EU policy is pending, which was transferred to the Portuguese Presidency that took over from the German one on 1/1/2021. It is one of the most hotly contested issues facing Europe at a time when there are member states that call for ‘sealing off’ Europe to refugees and immigrants and only accepting people of specific ethnicities, cultures, and religions, according to Santos Silva, Portugal’s foreign minister (Financial Times, 2/1/2021, p.2).

[12] What’s striking to me is that refugee children wish to leave Greece for the very same reasons that Greek young people do: due to the lack of a framework.

[13] Like sailors, who never have a lot of stuff in their cabins.

[14] filmkommentaren.dk/blog/blogpost/4887, 25/1/2021

[15] The film Good Morning Mr Fotis was not funded by the Ministry of Education. I addressed a registered letter to the Minister, Niki Kerameos, on 4/2/2021, to inform her about the film and to suggest that Fotis Psycharis be honoured for his overall contribution as a teacher. I have not received a response nor has Fotis received any acknowledgement of his work – at a time when the need for teacher evaluation is increasingly felt.

[16] See article footnote 5.

[17] In early March 2020, some 7,000 persons live in Kara Tepe, the camp that replaced Moria. More than 2,120 are children; 697 are four years and younger. ‘The Desperate Children of Moria’, Der Spiegel (in English), 1/4/2021, https://www.spiegel.de/international.

[18] At the time of writing (March 2021), Greece makes efforts to send back to Turkey 1,450 asylum-seekers whose application has been rejected. According to the United Nations World Food Program, 12.4 million Syrians live in famine and pressure Turkey in the form of an influx of migrants (currently holding, according to official UN figures, 3.6 million from Syria and another 300,000 from elsewhere). See Handelsblatt, 14/3/2021, ‘Deutschland und die Türkei verhandeln neuen Flüchtlingspakt – Griechenland verärgert, Die Türkei hält Geflüchtete von der Weiterreise in die EU ab. Das soll sie für Geld und Zugeständnisse weiter tun. Das birgt diplomatische Probleme.’ [Germany and Turkey negotiate new immigration agreement – Greece is annoyed, Turkey restrains migratory flows from continuing their journey to the EU. To continue doing so, it is asking for money and benefits. This creates diplomatic problems.]

[19] Handelsblatt: ‘New refugee deal negotiated by Germany and Turkey – “Greece upset”. According to information cited by Handelsblatt, the points that are most likely to spoil a new agreement are being discussed.’ To Vima newspaper, 14/03/2021